A City of Commerce in a Time of Plague

by Sary Zananiri

“The area around Jerusalem’s New Gate has always felt homely to me, though perhaps not home. It’s where my father went to school, it’s where my grandfather was born and it’s one of the few parts of the Old City where I feel a sense of the social fabric that once existed, albeit amongst much change.”

- Notes 20th March, 2020

These images were taken on my last walk through the Old City of Jerusalem on the afternoon of April 5th, 2020 (Latin Palm Sunday). I had been undertaking a residency at the Al Mamal Foundation, located in the Old City. It was a few hours before I flew back to The Netherlands on a circuitous route via Minsk. My plane tickets back had been repeatedly cancelled and rebooked due to the growing COVID 19 pandemic. Flights had become scarce.

…

While Jerusalem is commonly thought of as a global spiritual capital beleaguered by political contestation, I have always thought of it as a city of commerce. In recent years, my research has focused on the photography of Palestine as well as the production of souvenirs and religious goods. I have expended much thought on the ways in which Palestinian artists, photographers and merchants addressed the significant tourism industry – both religious and otherwise – as modes of Palestinian cultural diplomacy.

Indeed, the histories of Palestinian cultural production are strongly influenced by and entwined with the global market for biblical narrative. Palestinian carved mother of pearl production in the nineteenth century was a transnational market with Palestinian trading outposts from Kiev to Paris and Port-au-Prince to Manilla, underscoring a careful marketing of their ‘Holy Land’ origins (Norris 2013).

Likewise, the biblical formed a particularised genre in photography for both local studios and the steady flow of Western photographers visiting the ‘Holy Land’. Biblified photography addressed a global market, tracing religious sites, putative or otherwise, often absenting the modern city and the people that inhabited it in favour of images projecting an ostensibly ancient past (Nassar 2006).

The Old City of the modern era has long been a centre of activity, merchants jostling for customers among the devout and secular alike. As early as the 1850s, visitors to the city commented on the inauthentic hub of tourism that Jerusalem had become, preferring the wild majesty of the Jordan valley to the modernity of Jerusalem (Cocks 2010). Later memoirs spoke to a plethora of devotional goods and souvenirs marketed to tourists and pilgrims addressing the multiple price points of the market (Lind, unpublished manuscript, Library of Congress).

By April of this year, Jerusalem had been quiet for weeks. The stream of tourists that typically populate the streets had dwindled rapidly, leaving the hubbub of the city greatly reduced. Initially optimistic souvenir vendors slowly closed their doors and shuttered their shops around the Holy Sepulchre as Israeli police monitored who entered and left the city gates. Finally, the remaining restaurants and cafes shut with the onset of the mandated lockdown.

Commerce in the city had all but stopped, except for the handful of small supermarkets on the Via Dolorosa, which always seem to have a steady buzz of people shopping for a few loaves of bread or a bottle of milk, maybe for the third time that day. Or that other type of shopper who buys several weeks of groceries in one go, freezing bread and stocking up on staples, cans and pickles.

Once a week, I left my apartment to shop for groceries. A few doors from the supermarket, a room with an open door was filled with bread and plastic bottles of olive oil, attended by young Palestinian men wearing masks, awaiting distribution. The city was already preparing for crisis, accommodating even its poorest inhabitants’ needs. I think about the famine of World War I, and the decisions about whether to stay or go so many had made in this city before and since. Walking through the streets of the Old City, now empty and boarded up, a city once filled with commerce and souvenirs, a city that has sold itself to tourists and pilgrims for hundreds of years, I was haunted.

At first, it felt like a precious time to be in Jerusalem. It was a different version of the city, one that was local, with streets populated by Jerusalemite accented Arabic. I messaged with a friend in Shuafat who, like me, was also stranded in Jerusalem. We thought about the ironies of what this lockdown-mediated ‘return’ of sorts meant to us and our fraught relationships to the city. It was a strange moment to be ‘trapped’ in Jerusalem, a city that many Palestinians will never have the opportunity to visit. We romanticised the localisation that COVID had brought, the sense of community that had become palpable and the opportunities for building our tenuous connection to the city that the lockdown brought. Another friend remarked that they had not seen the city so quiet since the Second Intifada.

The question of what constitutes an authentic version of Jerusalem has lingered long in my thoughts these last months. Is an authentic version of the city one where its inhabitants have a sense of its own place locally? Perhaps it is a city whose global importance its people struggle to live up to, despite its tangible rewards? The very significant social and economic disruption COVID presents to the city’s tourism economy hinted at Jerusalem as it might have been before it became an Ottoman administrative centre, with all the trappings of wealth and connection that accompanied its redesignation in the 19th century.

Although it is too trite and simplistic to talk of the situation in Jerusalem within frameworks of religion or conflict, both are present in different ways. The anxiety I felt about whether to stay was tempered by questions of visas, global and local movement restrictions and a disrupted research project. I had spent much of my time on the rooftop of my apartment watching the stillness of the Old City.

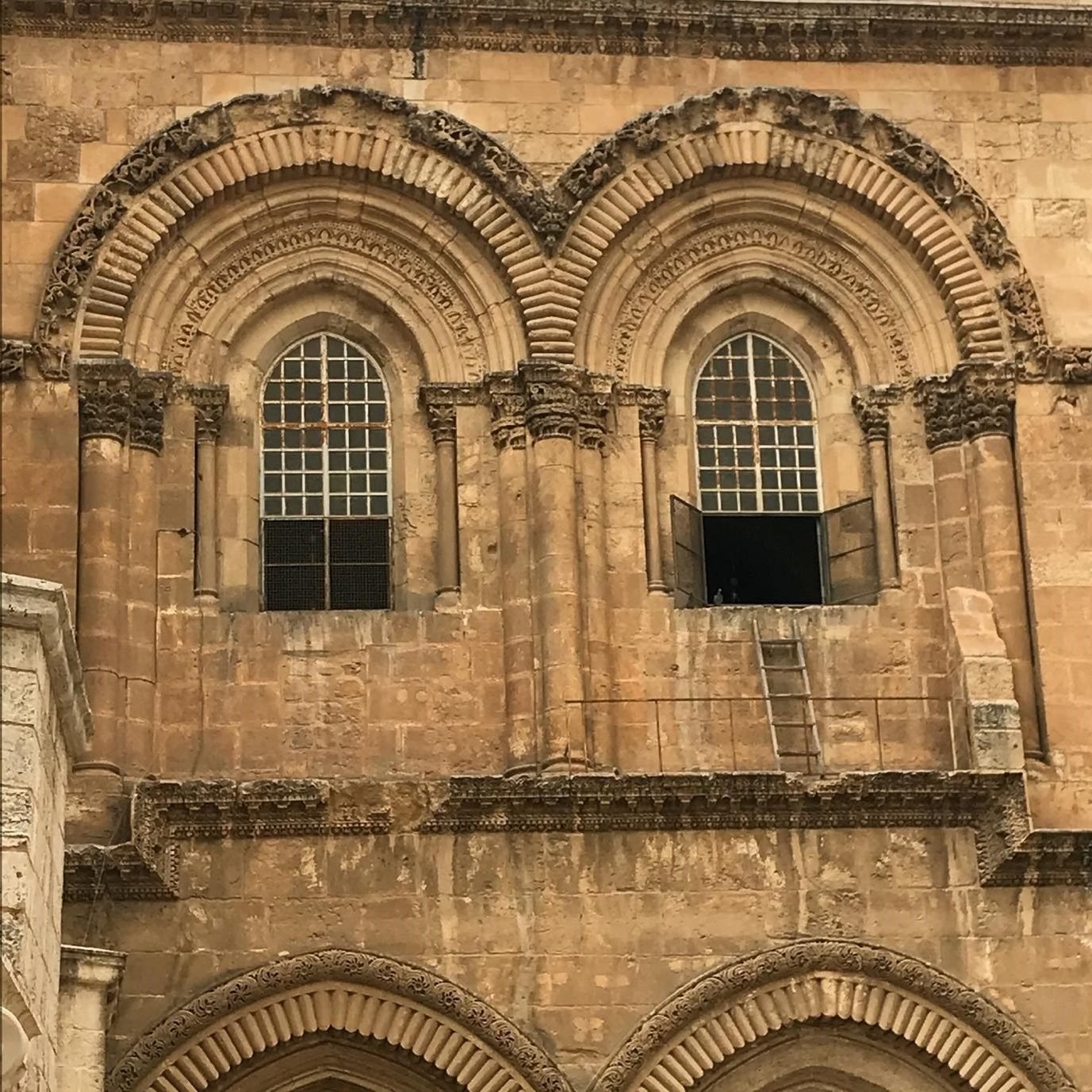

The day I left was Latin Palm Sunday. I went for a walk through the city, contemplating my decision to finally leave and the odd route I would have to take. Everything was closed. Even the door to the Holy Sepulchre was locked. Seemingly deserted, but for the lilt of priestly practices emanating from inside – one of the few sounds to be heard across the city – from those select Holy folk in the inner sanctum of Christianity. Another man, also Palestinian, wandered into the entry courtyard of the church from the opposite side. He did exactly what I did. He took a photo and left. This city never ceases to compel the actions that a religious Disneyland should, even during a plague of what seems like biblical proportions. And that ladder, that symbol of fractuosity rather than consensus, still leaned beneath the upper window of the façade.

The photos I took of the empty streets that day seem to hark back to those biblified images: the lack of people, the empty Old City, the closed shops, churches and institutions. I still feel confronted by these images of emptiness. The logic of the colonial visuality produced by biblified imaging (Zananiri 2016) looms heavily overthese photos.

I went back to my apartment to pack my belongings, an action I had undertaken many times before and undertaken by many before me in different circumstances. I sat on the rooftop. It is not metaphorical when I say that the view across the Old City from the roof top of my apartment was a front row seat to an apocalypse that will continue to unfold. The collapsing of time in that space was unnerving as I contemplated the future of the city, and the news since has fared no better.

…

The author would like to thank Nayrouz Abu Hatoum and Sarah Ihmoud for their encouragement and generous comments on this article, Micaela Sahhar for her comments and efforts on an earlier draft and Hadeel Assali for suggesting the initial submission. I would also like to thank the Al Mamal Foundation for hosting me, especially given the difficulties posed by COVID and Jumana Manna, my wonderful interlocutor during the lockdown.

…

Cocks, H. G. "The Discovery of Sodom, 1851." Representations (Berkeley, Calif.) 112, no. 1 (2010): 1-26.

Lind, Lars Jerusalem Before Zionism, unpublished manuscript, Library of Congress

Nassar, Issam. "'Biblification' in the Service of Colonialism." Third Text: The Conflict and Contemporary Visual Culture in PALESTINE & ISRAEL 20, no. 3-4 (2006): 317-26.

Norris, Jacob. "Exporting the Holy Land: Artisans and Merchant Migrants in Ottoman-Era Bethlehem." Mashriq & Mahjar 1, no. 2 (2013), Vol.1 (2).

Zananiri, Sary “From Still to Moving Image: Shifting Representation of Jerusalem and Palestinians in the Western Biblical Imaginary” Jerusalem Quarterly, Issue 67, Autumn 2016

Sary Zananiri is an artist and cultural historian. He completed a PhD in Fine Arts at Monash University in 2014 looking at the biblified colonial imaging of the Palestinian landscape from 1839 to 1948. His research interests sit at the intersection of colonialism, indigeneity, religious narrative and visual culture.

He has two forthcoming co-edited volumes with Karène Sanchez Summerer: European Cultural Diplomacy and Arab Christians in Palestine: Between Contention and Connection (Palgrave McMillan, December 2020)and Imaging and Imagining Palestine: Photography, Modernity and the Biblical Lens (Brill, Spring 2021).

He exhibits and curates widely, most recently at the Rijksmuseum Oudheden (May-October 2020), the Mawjoudin Queer Film Festival, Tunis (postponed until 2021) and Der Haus Der Kunst der Welt, Berlin (June 2019).

He was an Associate Lecturer in the Fine Art department at Monash University in Melbourne (2014-18) and a co-director of the Palestinian Film Festival, Australia (2016-18). He is currently a Postdoctoral Researcher on the NWO funded project CrossRoads: European Cultural Diplomacy and Arab Christians in Palestine 1918-1948 and the Netherlands Institute for the Near East at Leiden University.