Diary: An Inventory of Rejections

By Hadeel Assali | July 2023 [Updated 15 August 2023]

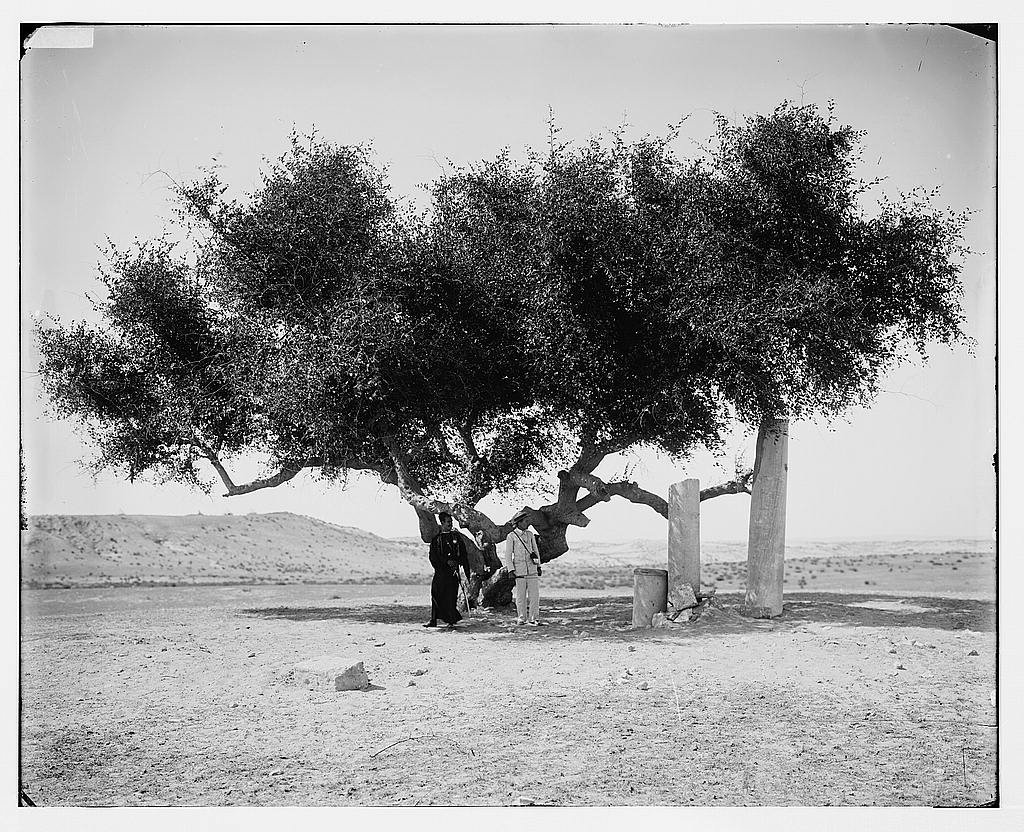

Rafah Border as Tree. Image credit: Library of Congress

Author’s Note

This is my first time collecting in one place all of my failed attempts to access Gaza through ‘official’ means. The total came to nine rejections for entry since 2005. We Palestinians tire of these stories – our own and others.’ Everyone has them (to very different degrees), and it is unpleasant to recount them or to relive someone else’s experience.1 I am a perpetual list-maker; lists give order to things and the (false) sense of having things under control. Maybe this is why it felt easiest to offer an inventory. In drawing this list up from diaries, letters, fieldnotes, and my travel companions’ memories, I am stunned at how much I had forgotten – or absorbed. I am still shocked at how normalized and mundane these experiences are for Palestinians. Everyone would rather just tuck away and forget the feelings of utter powerlessness at borders and checkpoints. But maybe some forms of remembering – such as this list – will serve some purpose, even if simply to contribute to the inventory that Edward Said advised all Palestinians to keep and document the ongoing dispossession all Palestinians face by Israel and its complicit institutions.2

Ethnography generally calls for a sustained presence in the place of study. My ethnographic research was blocked and fragmented by the colonial fragmentation of Gaza. Unexpectedly, the political blockages I faced (along with a stubborn refusal to give up) led to new ways of seeing things. In the process, I learned that despite the fragmentations and blockades, many kinds of relations persist and extend the geographies of Gaza well beyond the most militarized and deadly colonial boundaries. While these forms of resistance of maintaining relations deserve to be seen and recognized and even celebrated, the forces aimed at severing these relations are immense and mustn’t be normalized. Even for Palestinians with US citizenship, it is extraordinarily difficult to access (let alone study) our own communities due to the Israeli-state imposed restrictions on our freedom of movement and due to many other governments’ complicity. And yet the Palestinian-American experience pales in comparison to the obstacles those on the inside face as a result of their Israeli-imposed IDs. For this reason, it feels indulgent to tell my story of the obstacles I faced while conducting research; however, anthropology teaches us that positionality matters in the production of knowledge. Thus, this inventory includes details about my changing political status to demonstrate that despite having US citizenship, and despite having the support of a major Ivy League institution, my familial ties to Palestine expose me to political blockages imposed by the Israeli military occupation.

1. See, for example, anthropologist Rema Hammami’s ethnography of checkpoint experiences in the West Bank. This offers a much more poignant picture of what Palestinians living under Israeli military occupation suffer and navigate on a daily basis; and while it is different from the diasporic Palestinians’ experience at border crossings, it resonates with the refusal to wallow in these narratives of suffering. We would rather move on. “On (not) suffering at the checkpoint; Palestinian narrative strategies of surviving Israel’s carceral geography,” May 2015, read here.

2. Said, Edward. ‘Zionism from the Standpoint of Its Victims’. Social Text 1 (Winter 1979): 7-58.

1999

I was still technically stateless but held a US green card since 1996. For travel abroad, I was issued a US Re-Entry Permit – it looks like a white passport. That summer, the State of Israel approved my three-month single-entry visa. I used it to attend a study abroad program at Birzeit University, which my university at the time (the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) refused to recognize. Law professor Francis Boyle threatened to sue on my behalf, and the University changed its position. I was based in the West Bank that summer, but made frequent trips to Gaza, which was only a one-hour taxi ride away. Each trip required passing through the infamous Erez military checkpoint, where Palestinian day laborers from Gaza are forced to pass through humiliation and abuse at the hands of Israeli soldiers while going to and from work inside Israel. I was allowed to pass through the “VIP” area.

It was ‘a good year,’ as many Palestinians say, when Gaza was a little less of a prison. I had a magical time with my paternal aunts, uncles, and cousins in Gaza City. My visit also coincided with my maternal grandmother’s arrival from Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. She and her brother picked me up along with a box of figs by the beach road, which we took down to al-Maghazi camp, where a sea of relatives had gathered and preparations for a wedding were underway. I remember smiling faces, beach outings, shopping markets of all kinds, mu’ajanaat (baked treats), Kazim’s ice cream and barrad (a local yellow iced drink), sardines fried outdoors during power cuts, fresh lemonade on my aunt’s balcony, and so many other treats that summer.

2002

I became a US citizen after having been in the United States since 1980. I also started working as an engineer, and in my free time I organized cultural-educational and political events around the question of Palestine in Chicago, then in Houston after I moved there in 2003.

2005

That winter break, my brother and I went to Palestine. I recently asked him what possessed us to go at that time; he replied: “to smoke cigarettes and visit Arafat’s grave. We were thinking about going to Gaza but the Zionists lost their minds.” We flew to Amman and crossed the bridge over the River Jordan to the West Bank. In an email to friends and family, I wrote the following about the border experience:

the jordanian side was easy, although I hear in the high season it can be horrendous. the bus drove us through semi-arid rich brown rolling hills. We arrived at the first checkpoint where two soldiers searched under the bus with long poles with mirrors on the end while third stood with his finger on the trigger of his gun. We were allowed to go on to the next point where we all unboarded the bus and waited. So many female soldiers. A young palestinian man pushing a cart was ordered to uncover his cart, then open his jacket, then open his vest... my brother and I were called over to be questioned. Why are you here, where are you going, etc etc. then we were sent to “pasport control” where they were sending back a palestinian family who had come all the way from italy because their daughter’s birth certificate was not on the right form... my turn. No, I will not speak arabic with them. When I mentioned gaza, the female soldier flipped out and took our passports to some back room. Another female soldier interrogated us, asked to see our return tickets, made us wait another hour or so, then finally granted us a 2-week visa. When I asked why we didn’t get the typical 3-month visa, another responded “we don’t give that to everyone”... after having our things searched, we were finally off to jerusalem.

We stayed with a friend and her family in Shu’fat, in Jerusalem, and we spent time at the Ibdaa Cultural Center in Dheisheh Camp in Bethlehem. Everyone tried to help us figure out how to get permission to enter Gaza, but nothing materialized. So near yet so far. I remember sad phone calls with relatives there, including my uncle Hosam (whose voice is in this video.) We left, and during our transit in Amman, we met for the first time a great uncle named Mahmoud. I recently wrote about him here. I took a one-year leave from my job, founded the Houston Palestine Film Festival (HPFF), and began exploring writing and film and the possibilities of a career change.

2006

This time I stayed longer in the West Bank – the whole summer – and tried harder to access Gaza. I went to the Erez military checkpoint with another Palestinian-American friend who also has family in Gaza. Erez is the only civilian access point from the Israeli side, and we had been told by them over the phone to apply there in person for a permit to enter. After we submitted the paperwork, they did not return our passports and subjected us to a security check. This was not the VIP area I had experienced in 1999. This was 12 hours of incarceration, mostly within the gated barriers that Palestinian day laborers are subjected to. It looked like a cattle sorting area – concrete and metal everywhere. There was also a strip search. Our entry was rejected and we were released from custody at 2am.

Very soon after that experience, an Israeli soldier was abducted through a tunnel by the Palestinian resistance not far from where I was being held that day. From then on, “Gaza” landed like a curse word every time I crossed any Israeli-controlled border – whether at Ben Gurion airport, Taba, or the bridges to Jordan. My familial connection to Gaza, which is tracked in Israel’s extensive surveillance and ID system for Palestinians, added a minimum of four hours at every border crossing complete with detention, interrogations, and searches. I did not have an Israeli issued Palestinian ID because my father happened to be studying in Egypt when Israel occupied the West Bank and Gaza. For this reason, they could not restrict my freedom of movement the way they did West Bank and Gaza Palestinians, but I was forbidden from spending more than a few months (or weeks) at a time in Palestine. Once my visa expired, I returned to my job as an engineer in Texas.

2009

My mother, brother, sister, and I planned to visit relatives for the winter holiday break. My mother’s immediate family is in Saudi Arabia, but visas were not easy to acquire at that time. (Things have changed since Mohammad Bin Salman’s rule; before then, getting visitor visas were very difficult.) We decided to visit Palestine through Egypt. We wanted to give Gaza a try, but our trip coincided with a major protest by activists to open the border at Rafah. Egypt had been complicit in the siege on Gaza, and now with the protest it would be impossible to get in. We decided to go from south Sinai instead, through the Red Sea resort town of Taba. After several hours of the usual invasive “security” checks (we did not dare mention the idea of visiting Gaza) we explored as much as we could of the other parts of Palestine. We made many friends in Nazareth; my mom stuffed karshat, a dish of rice-stuffed lamb stomach, with a woman she met near our hostel.

2010

A cousin from my father’s side of the family was getting married in Amman. It was a chance to reconnect with many relatives at once, so I flew over from Houston. While there, I crossed the border and went back to Nazareth for a few days. I inquired about Gaza entry through Erez from afar – there were no options for entry. This time I was not allowed to return to Jordan on the same Allenby bridge I crossed earlier that week and instead sent further north to the Sheikh Hussein bridge. It was late by the time I got there; I was dreading the impending interrogation but resigned myself to it. There was a Palestinian family ahead of me in line; the mother looked inquisitively at me and asked what I was doing there. When I explained, she grabbed my passport and put it with theirs (they were Palestinians from Nazareth, “48 Palestinians” meaning those with Israeli citizenship). “You are with us,” she exclaimed, and smoothed my entry. They insisted I ride with them all the way to Amman, and they made sure to meet and reassure my waiting relatives.

2011

I joined a master’s program in anthropology at the New School in New York City and was supported and encouraged by senior anthropologists to focus my research on Gaza. I was later admitted to anthropology at Columbia University for doctoral study on the premise of a possible research project in Gaza.

2013

During the summer break, my mother and I visited family in Jordan. We had assumed it would be easier to visit Gaza from Egypt since Morsi was now in power. This would allow me to assess if ethnographic fieldwork there was feasible through Rafah since Erez crossing, on the other hand, remained sealed by Israel. However, by the time we left Amman, things in Egypt had started to become unstable. Morsi was suddenly removed from power in a coup lead by Sisi. During this ‘in-between’ time, it was unclear what this meant for the Rafah border crossing. We decided why not, let’s try. The drive from Cairo to Rafah was harrowing (there is one account about it here): “once we reached the closed Suez Canal bridge, we became aware of the heavy military presence in response to local insurgencies.” We passed through checkpoints where young soldiers were armed to the teeth, and locals warned us of bombings at tourist hotels in al-Arish when we stopped along the way. When we finally reached the Rafah border crossing, we were turned away by Egyptian border guards. We did successfully access Gaza through ‘unconventional’ means secured by our personal and familial relations, which eventually became a focus of my research.

2014

Late summer, I returned to Gaza after the Israeli bombings to check on relatives and to do fieldwork research preparations. Would I continue to be able to do research there? By now Sisi had fully stabilized his power in Egypt, and conditions in Rafah had changed drastically. I had unwittingly stepped into a warzone as the Egyptian military was cracking down on the tunnels and the alleged presence of ISIS in North Sinai. (Here is an account about the context and situation.) Despite the dangerous conditions, I was embraced by people on the Egyptian side of Rafah who felt Palestinian. I wished I could include them in my fieldwork. However, as conditions on the ground grew increasingly dangerous, it seemed unlikely that I could do fieldwork there or inside the Gaza Strip. But I went on hoping that things might change, or that Columbia University’s clout would ease access.

2017

My time for official ethnographic fieldwork had arrived. Would I be able to get in? I flew into Ben Gurion airport in Tel Aviv, and after the 4-hour interrogation/hold/search, went to the West Bank rather aimlessly. My PhD advisor, Mahmood Mamdani, sent an official letter on Columbia University letterhead to the Israeli military occupation (COGAT) requesting a permit for me to enter Gaza. No response. I tried the American embassy, who offered nothing. I spoke directly with the Palestinian Authority, who told me you had to have a “first degree relative” in Gaza to gain access – aunts, uncles, and cousins do not count; I tried friends with other governmental agency connections, humanitarian organizations, media passes – nothing. It was curious to me how some people get such easy access to Gaza. My family was also all hands on deck trying to find pathways for me; I was told to call this person and that; cousins in Gaza had me send my documents digitally so they could try to get a permit from the inside… nothing materialized. My cousin’s “permit from the inside” made me nervous – was he asking the Hamas government? How would that help my chances, especially as I was trying to stay under the radar? My research project feasibility looked bleak, but the beginning of my fieldwork coincided with the founding conference of Insaniyyat. The Palestinian anthropologists there advised me to stay with Gaza, to make use of my experiences thus far, and to get creative. I began to hover around Gaza’s edges, renting a car and driving deeper south. I began to realize Gaza’s geographies – historically, socially, ecologically, and so on – extended beyond “The Gaza Strip” in unexpected ways. I had to change my own thinking.

I traveled out of Palestine for a bit of inspiration – my husband joined me. We left a suitcase behind and went for a vipassana meditation retreat in Sri Lanka, the Cu Chi tunnels in Vietnam, and finally a sea journey across the Indian Ocean brought us back to Egypt. I realized it was time to try new approaches. I still attempted the official routes in Egypt, knowing chances were slim-to-none. Family and friends insisted, “with an American passport, it should be easy. Just go to the American embassy in Cairo.” Nothing. The Palestinian embassy in Cairo has no power to grant access either. I even asked directly and in-person at Egypt’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I wrote the following in an email as an update to one of my advisors, Lila Abu-Lughod:

I have met with the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs Palestine Office (i had no idea there was one, xxxx’s father helped make that happen). The minister (Bahaa el-Desouky) went on and on about how much they love Gaza and how Gazans assimilate much easier in Egypt than West Bankers because of the proximity of cultures, and how he too has relatives there and lived there; he had moved there right before "that intifada of yours." One thing I gathered from conversations with them is that they seem to love Dahlan... Also, in the main office are two women, a deputy minister and an intern, and can you believe they had BDS materials there - it was like a little activist office - in that big building at Maspero! I am meeting with them again before I leave to get a sense on what might be possible with them for when I return; they seemed open and friendly but I am aware that could be playing with fire. I am asking them at every step of the way for them to tell me how to make sure I do not overstep any security lines, and I'm hoping they can give me some hints about what is going to be happening in the near future. They were the ones who told me the Rafah crossing is closed now because they are building a big brand new Rafah crossing "to alleviate the suffering of the Palestinians" (...) and it was clear that they do not make decisions on when the border is open (the army calls all the shots). So I will see them again on Sunday and see what else is possible. Lucky for me, the intern that works there is an AUC graduate student and explained to them the IRB thing and made me sound really legit (which I am of course).

I also met with the Palestinian embassy here. Fancy building in Dokki area and now they are planning on building a huge complex out in taggamo3 area. I could possibly spend some time with them getting to know what they are up to especially as this Dahlan-Hamas connection materializes, what will their role be? (i don't exactly understand what is their role now, to be honest.)

My advisors suggested focusing my research on all these closed roads to Gaza, and they were right – several books could be written about these experiences. I was interested in more than this, however, and turned my attention to north Sinai and the Egyptian side of Rafah – a forbidden topic in Egypt. It became more apparent how deeply dependent Gaza is on conditions in Egypt. I did discrete ethnographic fieldwork in several parts of Egypt; Gaza connections were everywhere, even in south Sinai.

While I was doing fieldwork, I sent my husband for the suitcase we had left in Bethlehem before our journey. It should have been an easy trip for him; he is not Palestinian and has a US passport. There are tour buses full of Russians that regularly go straight from south Sinai tourist areas (Dahab or Sharm el-Sheikh) to Jerusalem, then Bethlehem, and back to Sinai. It is a 48-hour trip; he planned to scoop the suitcase and return. Instead, he was stopped and interrogated at the Israeli border at Taba for so long that the bus left him. They asked him about me, and he was not granted a visa. Later, when we returned to New York, he was held and interrogated at JFK airport about what happened at the border in Taba. Again they asked him about me (even though I was there in the waiting area). Once, he and I were taken off a domestic flight for extra security checks. After that, I decided to apply for the Global Entry program to see what would happen through that security process. I figured if they had something to say to me, they could say it to my face? The opportunity did not arise. My Global Entry application was approved, and these things stopped happening to both of us at US airports.

2018

At the beginning of the year, I returned to Egypt and hired a researcher inside the Gaza Strip. She and I became remote fieldwork companions. Her contacts in Gaza connected me with their contacts in different parts of Egypt and vice versa. Together, we navigated social worlds that spilled over even the most militarized of borders. I conducted more in-depth ethnographic fieldwork with people displaced from Rafah to different parts of Egypt, all of whom had relations in Gaza. Accessing north Sinai and Rafah was completely off limits at that time due to Egypt’s “war on terror,” which was in full swing, so I went to south Sinai and continued my research there. Later it became openly admitted that Israel was participating in the bombing of north Sinai.

2019

The last territorial fragment that I wanted to suture ethnographically to the geography of Gaza were the vast areas to the east and south east, what Salman Abu-Sitta calls “the forgotten half of Palestine.” I traveled there with my mother and my husband. The Israeli military at the border took extra interest in him; he refused to give over his phone and told them to decide already. We were eventually granted entry. Again, there was no way to access the Gaza Strip. But once in southern Palestine, we covered as much ground as we could. We were welcomed into Rahat with such hospitality – mansaf and other rice dishes, fresh-baked breads, mashawi (grilled meats), and endless amounts of tea. Everyone we met seemed to have relatives in the Gaza Strip. We join them on visits to Israeli national parks in southern Palestine, a region which Israel renamed the “Negev.” These parks are the lands from which the residents of Rahat and other forced townships were dispossessed. Khobeiza (common mallow) was in season, and the women were out picking it – as likely had been done in the region for centuries. Although everyone always had it cooking, they made me swear secrecy when I requested we have khobeiza over the fancier dishes.

I haven’t been back since.

Hadeel Assali is a Palestinian-American who tries to do research in Gaza.

Views of the border near the southernmost tip of Palestine and Sinai near Um Rashrash (renamed Eilat by Israel). All photos taken in 2019 by the author.